What is Afro-Cuban Folkloric Music and Dance?

Afro-Cuban Folkloric Music, as referred to by the Cuban Music Project and Roberto Borrell, is the music that originally came from Africa through the slave trade to Cuba. Once in Cuba, it melded with the Catholic religion and the Spanish, French and Haitian cultures.

It is often religious in nature but not necessarily. The music is almost always accompanied by song and dance. It may be sung in the languages of Yorùbá, Congolese, Abakwá or a dialect of Spanish. In its inception it was used as a way to practice and preserve religion or culture in Cuba. In the 20th Century Afro-Cuban music and dance started to appear as performance pieces in shows and concert venues.

One could divide the musical traditions between those that are sacred and those that are secular. The sacred music, or music belonging to a religious practice, is connected to the religions of the Yoruba, Palo, Vodú and the Arará. More often then not, these religions were connected to specific tribes in Africa and then found themselves recreated in certain regions of Cuba.

Yoruba

Yoruba is the most widely spread and practiced Afro-Cuban religion in Cuba. It also is referred to as Santería and Lucumi. The Yoruba people were large powerful tribes that developed before the 8th Century in western Africa including what is now southwestern Nigeria. The Yoruba were brought over from Africa since the beginning of slavery but they were also one of the last tribes to be brought to Cuba. The number of slaves greatly increased in the mid-19th Century in Cuba as most of the other nations had already abolished slavery. Yoruba, as a religion and a tribe, still exists in Africa but Santería, the mixture of Yoruba with Catholism, was developed in Cuba.

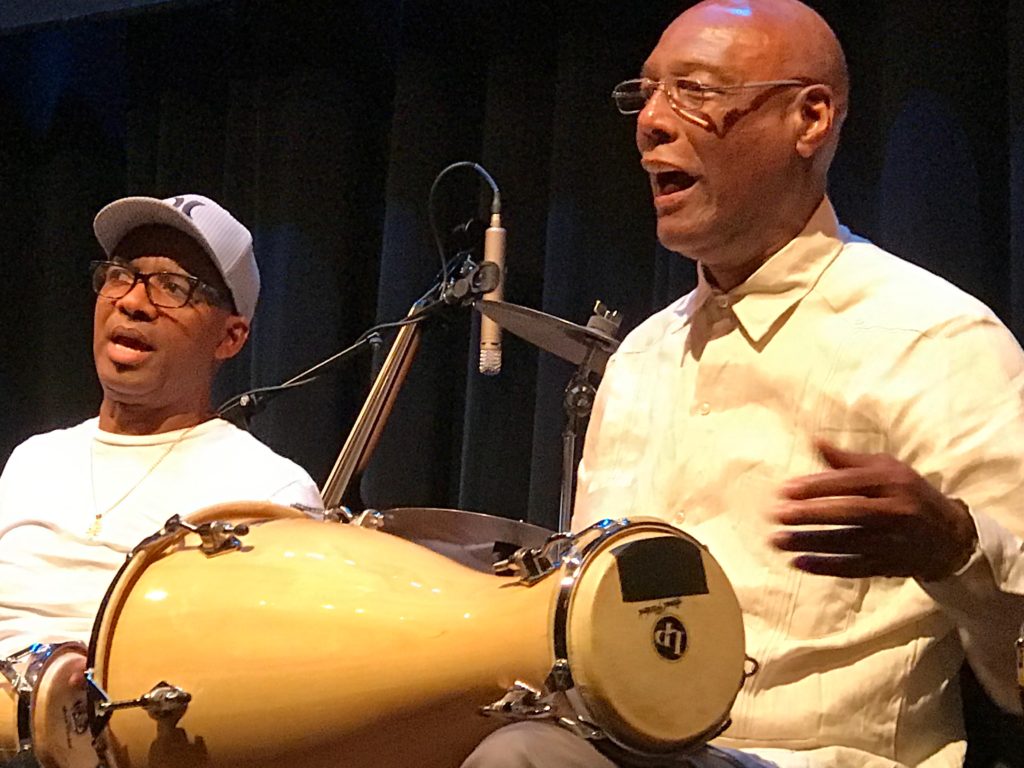

The music of Santería in Cuba is a highly complex. The drums, the Batá, are long and wide like an hourglass on its side. They are played in sets of three, the Iyá, the Itótele and the Okónkolo. The Iyá is considered the mother and is the lead drum, the Itótele , slightly smaller in size, is responsible for answering to the Iyá and the Okónkolo, the smallest of the three, keeps the rhythm. Traditional drums used in ceremonies or “fundamento” are carved out of a solid piece of wood. They are treated as sacred objects and are wrapped and protected by ceremonies and blessings. Women are not allowed to touch drums designated as “fundamento”.

There are dozens of main polyrhythmic rhythms in Santería to start with and several hundreds of songs. The music, dance and song are based on a pantheon of human-like deities called Orishas. Each Orisha has its own character, stories, rhythms, songs, dances, colors and food. The religious ceremonies are usually held in honor of an Orisha and are lead by the main singer who is called the Akpwon.

Palo

The religion of Palo is less practiced in Cuba but still exits. It consists of slaves brought from the Congo Basin, a region of Central Africa. Their language came from the Bantu peoples, called Congolese in Cuba, and is strongly mixed with Spanish when used in ceremonies and songs. The rhythms in Palo are not as complex as in Santería and the dance is stronger and more forceful. Palo, the music, is usually played on yuka drums, and the not on the sacred Batá used in Santería.

Arará

Arará is an African based religion found in Cuba originating from the Ewe-Fon of the Dahomey people in Africa. In Cuba it mixed with the Santeria practices and the dances of Haitian Vodou. Arará practice is centered in Matanzas.

Cuban Vodú

Cuban Vodú is indigenous to Cuba but influenced by Haitian Vodou. It also originally came from a very small area of the Kingdom of Dahomey consisting of mostly Fon people. The Dahomey Kingdom was known for its warriors, both men and women, and was given the nickname “black Sparta” by Europeans. Now that area in African is recognized as Benin.

Each of these religions have a strong musical identity that is still found in Cuba today, both in religious ceremonies and as performance on the stage. There are three very influential non-sacred musical genres in Cuba that are widely practiced and performed.

Abakuá

The first, in time and probably importance, is the Abakuá The Abakuá came from the coast of Nigeria close to Camaroon from the city of Calibar. In Cuba it exists as as an all-male honor society similar to that of the Masons, demanding long initiation ceremonies and a highly structured hierarchy involving different houses, lodges or “games”. Only men from Havana or Matanzas are allowed to be part of the Abakuá. Its musical traditions and rhythms can be traced throughout all African based genres of Cuban music. Today it shows up in many stage performances because of its theatrical costuming and unusual dance movement. In a show you will often see a Morua leading the Ireme around the aisles and onto stage. The Ireme is completely covered in a bright, often checkered costume with a cone shaped headpiece topped with straw. It is difficult to perform because of the complexity of the rhythm and because there are only tiny slots in the head piece to breathe and see.

Guaguancó

The other very popular genre of Cuban secular music is Rumba or more properly known as Guaguancó. Once relegated to the poor black neighborhoods by the docks and in the solars of the cities, Rumba can be seen today in any Cuban dance club, in almost every show presenting Afro-Cuban music and is enjoyed all over the world. This should not be confused with the Rhumba style of Ballroom Dance.

Guaguancó is the name of the rhythm and the party was called a Rumba. It started as a social dance in the Afro-Cuban communities of Havana and Matanzas. Originally it was played on “cajas”, boxes, with the Clave and a singer. Really it was just a street party where they played the Guaguancó rhythm on local instruments and danced. The Rumba has three rhythms; Yambú, traditionally slower and more graceful, Guaguancó, where the dancers play a mating game like a chicken and a rooster, and Columbia, which is fast and danced traditionally by men. Rumba is lively, sexy and a lot of fun. No wonder it has caught on around the world!

Conga

And then there is Caranaval, cannot forget Carnaval and the Conga. Conga is the music, Caranval is the event and Comparsa is the group, like a carnival contingent. Originally the slaves and free blacks were allowed to parade around the neighborhood playing their music on only one day of the year, Three Kings Day. This was the beginning of Carnaval in Cuba. Before that, slaves had been allowed to gather inside houses called Cabildos. They were similar to a community center where members of the same tribes who shared related languages and religions were allowed to gather. Then on All Kings Day they were allowed to take their music, their dance and their culture out into the streets.

Later, when times were a bit more lenient, the comparsas were created in neighborhoods. Each had a theme, colors, songs and even a story. There are the Jardineras from Jesús Maria, who celebrate a garden in the neighborhood, the Los Dandys from Belén, dressed in fancy French lace sleeves and velvet, and the oldest known comparsa, El Alacrán from El Cerro, named after the scorpion, demonstrates the tedious work of slaves cutting sugar cane. Comparsas were often over a hundred people, including dancers, musicians, farolas and models. In the 20th Century the white people joined Carnaval dressed in their Sunday finest riding on large decorated floats. When Fidel Castro came into power after the Revolution in 1959, Carnaval changed again and the floats were represented by labor unions. During the last decade Carnaval was moved from its traditional time, at the end of Lent, to late July and the middle of August. Today Carnaval is still going strong in Havana and even stronger in Santiago de Cuba.